Born and raised in Northern California, Jim Coats grew up steeped in the pop music of the early to mid-60s, singing along to AM radio, 45 singles, and American Bandstand. Every Sunday night he watched the Ed Sullivan Show with his family, and there along with plate-spinners, performing bears, and the comedy of Wayne and Shuster he witnessed Elvis, the Beatles, the Lovin' Spoonful, Simon and Garfunkel, and other rock 'n' roll acts – and also got a glimpse of Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and that whole jazz scene. He had had a few early years of piano lessons, but at age 11 Jim got his first acoustic guitar for Christmas. By lucky chance, this happened just in time for our hero to drag the guitar into his standard-issue pre-teen period of withdrawal from human society. In music he found an ideal outlet for adolescent angst and rage, and he continues to recommend it for that purpose right up to this day.

Then in the late 70s someone gave Jim a David Grisman record, and his mind was completely blown. Okay, maybe his mind was kind of that way anyway. But this was music like he'd never heard before. Here were the tight harmonies of bluegrass and the swing of hot jazz . . . and that crazy mandolin: a melody instrument that could jump out in front of the rhythm guitar and play, really, just about anything. The Bay Area was the center of a budding Mandolin Universe, and Jim got himself an instrument: an old, well-worn mando with its brand name, "Strad-O-Lin," painstakingly spray-painted onto its peg head. Cheap, maybe, but its frets were in the right place. Jim did a little editorial work for Grisman's magazine, Mandolin World News ("It fits in your case!"), went to workshops, and got a chance to play casually with folks way beyond his league. That was a huge thrill in itself, and besides that those folks were tremendously accepting and encouraging. It was a kindness that he would never forget.

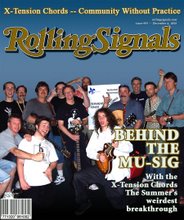

Over the years since, Jim has managed to keep a day job, marry, buy a house, raise a family, and still continue to play in a variety of groups and idioms: bluegrass with the Narrow Gauge String Band, Irish with Riggity Jig, recorder quartets with the Yolo County Windpipe Ensemble, folk and world music with the Redwood Grovers, and of course good ole rock 'n' roll with the ACE X-Tension Chords. "Getting a paying gig is great," Jim says, "but I'm like the musical equivalent of a junkie, I guess. I swear, I'd do it anyway, just for the endorphins. When we're all up there playing and singing together, it's like we're sharing a mind, the band and the audience, thinking the same thoughts, sharing the emotions. Groupthink. Groupfeel. It's the ultimate high. And, of course, there's the free beer and adulation, and sometimes you do get paid for it." What could be better?